By Mike Jay

From fairy-rings to Lewis Carroll’s Alice, mushrooms have long been entwined with the supernatural in art and literature. What might this say about past knowledge of hallucinogenic fungi? Mike Jay looks at early reports of mushroom-induced trips and how one species in particular became established as a stock motif of Victorian fairyland.

The first recorded mushroom trip in Britain took place in London’s Green Park on October 3, 1799. Like many such experiences before and since, it was accidental. A man identified in the subsequent medical report as “J. S.” was in the habit of gathering small mushrooms from the park on autumn mornings and cooking them up into a breakfast broth for his wife and young family. But this particular morning, an hour after they had finished it, everything began to turn very strange. J. S. noticed black spots and odd flashes of colour interrupting his vision; he became disorientated and had difficulty in standing and moving around. His family were complaining of stomach cramps and cold, numb extremities. The notion of poisonous toadstools leapt to his mind, and he staggered out into the streets to seek help, but within a hundred yards he had forgotten where he was going, or why, and was found wandering in a confused state.

By chance a physician named Everard Brande was passing through this part of town, and he was summoned to treat J. S. and his family. The scene he witnessed was so unusual that he wrote it up at length and published it in The Medical and Physical Journal a few months later.1 The family’s symptoms were rising and falling in giddy waves, their pupils dilated, their pulses fluttering, and their breathing laboured, periodically returning to normal before accelerating into another crisis. All were fixated on the fear that they were dying except for the youngest, the eight-year-old son named as “Edward S.”, whose symptoms were the strangest of all. He had eaten a large portion of the mushrooms and was “attacked with fits of immoderate laughter” which his parents’ threats could not subdue. He seemed to have been transported into another world, from which he would only return under duress to speak nonsense: “when roused and interrogated as to it, he answered indifferently, yes or no, as he did to every other question, evidently without any relation to what was asked”.

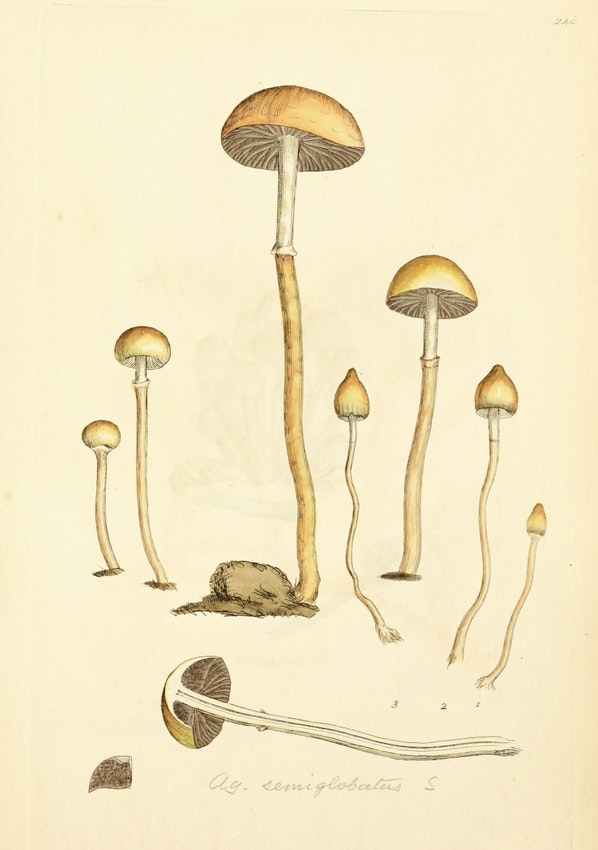

Dr Brande diagnosed the family’s condition as the “deleterious effects of a very common species of agaric [mushroom], not hitherto suspected to be poisonous”. Today, we can be more specific: this was intoxication by liberty caps (Psilocybe semilanceata), the “magic mushrooms” that grow plentifully across the hills, moors, commons, golf courses, and playing fields of Britain every autumn. The botanical illustrator James Sowerby, who was working on the third volume of his landmark Coloured Figures of English Fungi or Mushrooms (1803), interrupted his schedule to visit J. S. and identify the species in question. Sowerby’s illustration includes a cluster of unmistakable liberty caps, together with a similar-looking species (now recognised as a roundhead of the Stropharia genus). In his accompanying note, Sowerby emphasises that it was the pointy-headed variety (“with the pileus acuminated”) that “nearly proved fatal to a poor family in Piccadilly, London, who were so indiscreet as to stew a quantity” for breakfast.

Brande’s account of the J. S. family’s episode continued to be cited in Victorian drug literature for decades, yet the nineteenth century would come and go without any clear identification of the liberty cap as hallucinogenic. The psychedelic compound that had caused the mysterious derangement remained unknown until the 1950s when Albert Hoffman, the Swiss chemist who discovered LSD, turned his attention to the hallucinogenic mushrooms of Mexico. Psilocybin, LSD’s chemical cousin, was finally isolated from mushrooms in 1958, synthesised in a Swiss laboratory in 1959, and identified in the liberty cap in 1963.2

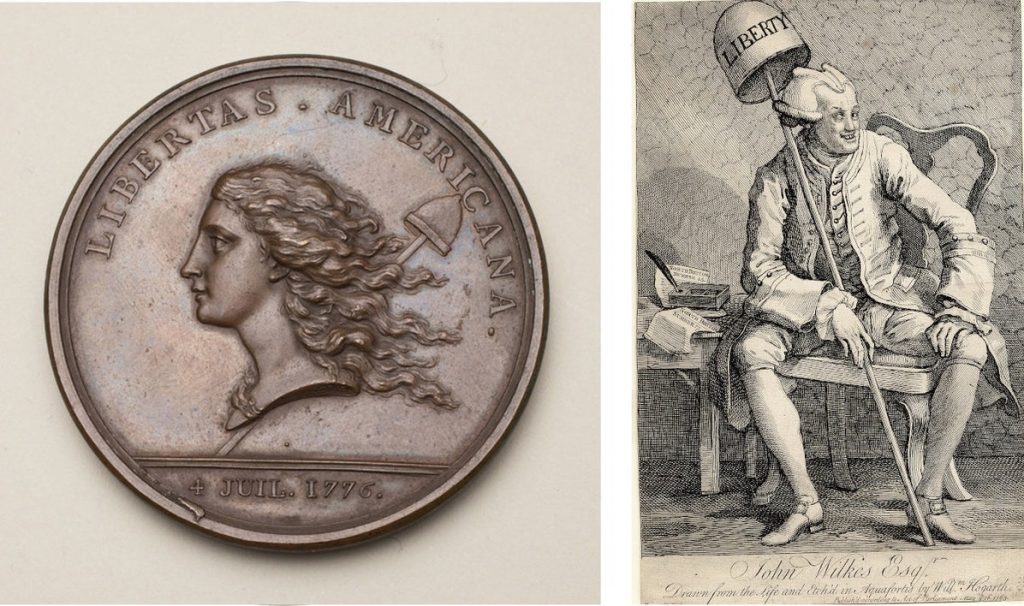

During the nineteenth century, the liberty cap took on a different set of associations, derived not from its visionary properties but its distinctive appearance. Samuel Taylor Coleridge seems to have been the first to suggest its common name in a short piece published in 1812 in Omniana, a miscellany co-written with Robert Southey. Coleridge was struck by that “common fungus, which so exactly represents the pole and cap of Liberty that it seems offered by Nature herself as the appropriate emblem of Gallic republicanism”.3 The cap of Liberty, or Phrygian cap, a peaked felt bonnet associated with the similar-looking pileus worn by freed slaves in the Roman empire, had become an icon of political freedom through the revolutionary movements of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. William of Orange included it as a symbol on a coin struck to celebrate his Glorious Revolution in 1688; the anti-monarchist MP John Wilkes holds it, mounted on its pole, in William Hogarth’s devilish caricature of 1763. It appears on a medal designed by Benjamin Franklin to commemorate July 4, 1776, under the banner LIBERTAS AMERICANA, and it was adopted during the French Revolution by the sans-culottes as their signature bonnet rouge. It was these associations — rather than its psychoactive properties, of which he shows no knowledge — that led Coleridge to celebrate it as the “mushroom Cap of Liberty”, a name that percolated through the many reprints of Omniana into nineteenth-century British culture, folklore, and botany.

While the liberty cap’s “magic” properties seemed to go largely unacknowledged, the idea that fungi could provoke hallucinations did begin to percolate more widely in Europe during the nineteenth century — though it became attached to a quite different species of mushroom. In parallel to a growing scientific interest in toxic and hallucinogenic fungi, a vast body of Victorian fairy lore connected mushrooms and toadstools with elves, pixies, hollow hills, and the unwitting transport of subjects to fairyland, a world of shifting perspectives seething with elemental spirits. The similarity of this otherworld to those engendered by plant psychedelics in New World cultures, where psilocybin-containing mushrooms have been used for millennia, is suggestive. Is it possible that the Victorian fairy tradition, beneath its innocent exterior, operated as a conduit for a hidden tradition of psychedelic knowledge? Were the authors of these fantastical narratives — Alice in Wonderland, for example — aware of the powers of certain mushrooms to lead unsuspecting visitors to enchanted lands? Were they, perhaps, even writing from personal experience?

The J. S. family’s trip in 1799 is a useful starting point for such enquiries. It shows liberty caps were growing in Britain at the time, and commonplace even in London’s parks. But also, the trip evidences that the mushroom’s hallucinogenic effects were unfamiliar, perhaps even unheard of: certainly unusual enough for a London physician to draw them to the attention of his learned colleagues. At the same time, however, scholars and naturalists were becoming more aware of the widespread use of plant intoxicants in non-western cultures. In 1762 Carl Linnaeus, the great taxonomist and father of modern botany, compiled the first-ever list of intoxicating plants: a monograph entitled Inebriantia, which assembled a global pharmacopoeia that extended from Europe (opium, henbane) to the Middle East (hashish, datura), South America (coca leaf), Asia (betel nut), and the Pacific (kava). The study of such plants was emerging from the margins of classical studies, ethnography, folklore, and medicine to become a subject in its own right.

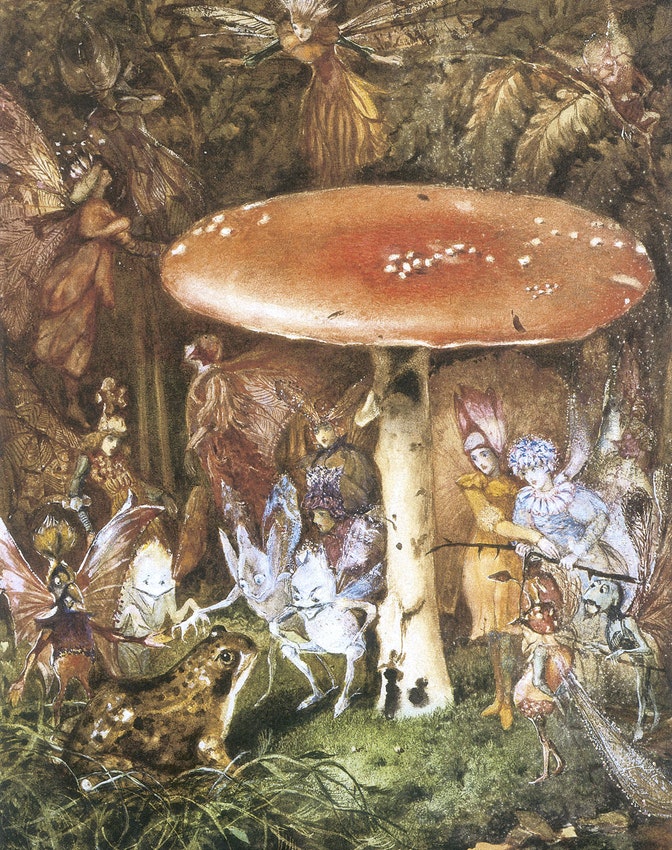

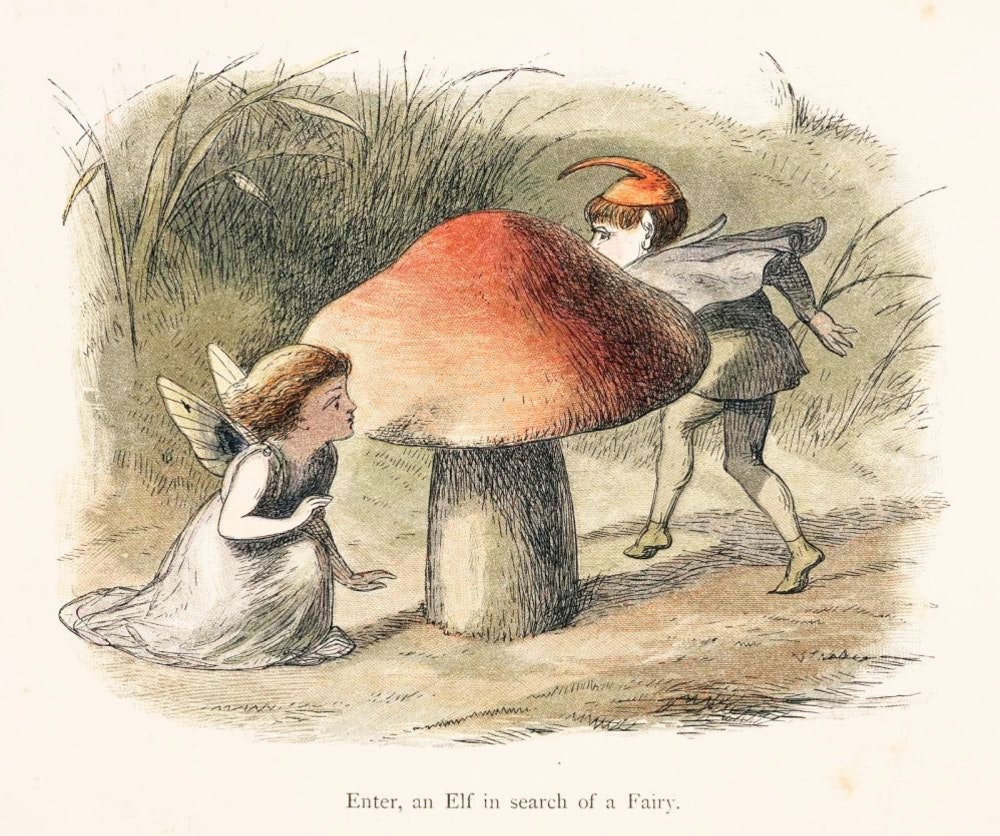

The interest in traditional cultures extended to European folklore. A new generation of folklore collectors, such as the Brothers Grimm, realised that the migration of peasant populations to the city was dismantling centuries of folk stories, songs, and oral histories with alarming rapidity. In Britain, Robert Southey was a prominent collector of vanishing folk traditions, soliciting and publishing examples offered by his readers. The Victorian fairy tradition, as it emerged, was imbued with a Romantic sensibility in which rustic traditions were no longer coarse and backward but picturesque and semi-sacred, an escape from industrial modernity into an ancient, often pagan land of enchantment. The subject lent itself to writers and artists who, under the guise of innocence, were able to explore sensual and erotic themes with a boldness off limits in more realistic genres and to reimagine the muddy and impoverished countryside through the prism of classical and Shakespearian scenes of playful nature spirits. The lore of plants and flowers was carefully curated and woven into supernatural tapestries of flower-fairies and enchanted woods, and mushrooms and toadstools popped up everywhere. Fairy rings and toadstool-dwelling elves were recycled through a pictorial culture of motif and decoration until they became emblematic of fairyland itself.

This magical allure marked a shift from previous depictions of Britain’s fungi. In herbals and medical texts from the Renaissance onwards, they had typically been associated with rot, dung-heaps, and poison. The new generation of folklorists, however, followed Coleridge in appreciating them. Thomas Keightley, whose survey The Fairy Mythology (1850) exerted much influence on the fictional fairy tradition, gives Welsh and Gaelic examples of traditional names for fungi which invoke elves and Puck. In Ireland, the Gaelic slang for mushrooms is “pookies”, which Keightley associated with the elemental nature spirit Pooka (hence Puck); it’s a term that persists in Irish drug culture today, although evidence for pre-modern Gaelic magic mushroom use remains elusive. At one point Keightley refers to “those pretty small delicate fungi, with their conical heads, which are named Fairy-mushrooms in Ireland, where they grow so plentifully”.4 This seems to describe the liberty cap, though Keightley, like Coleridge, focuses on the physical appearance of the mushroom and appears unaware of its psychedelic properties.

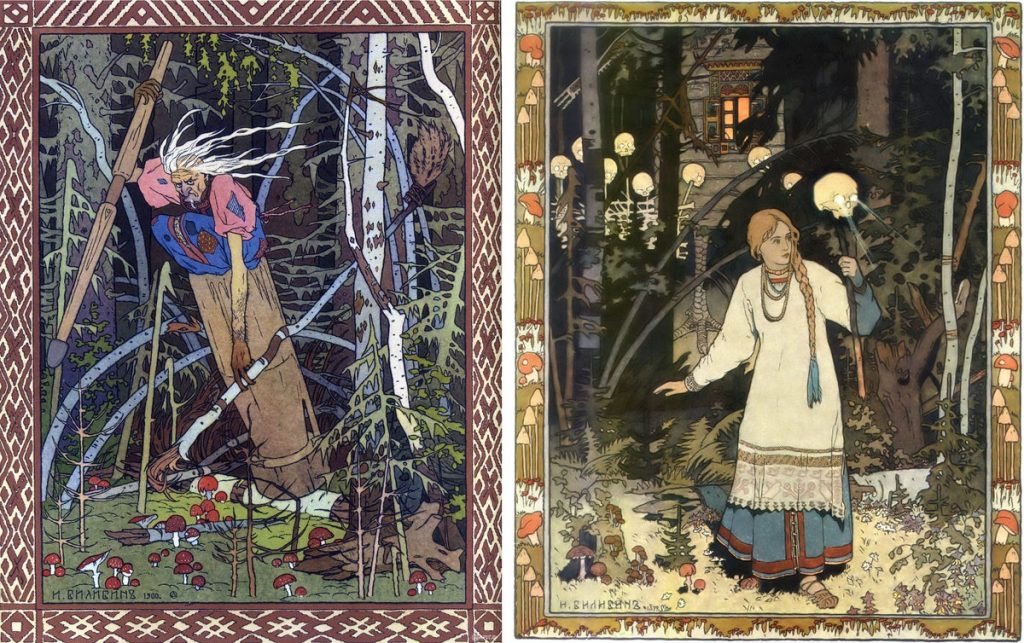

Despite its ubiquity, and occasional and tentative association with nature spirits, the mushroom that became the distinctive motif of fairyland was not the liberty cap but rather the spectacular red-and-white fly agaric (Amanita muscaria). The fly agaric is psychoactive but unlike the liberty cap, which delivers psilocybin in reliable doses, it contains a mix of alkaloids — muscarine, muscimol, ibotenic acid — which generate an unpredictable and toxic cocktail of effects. These can include wooziness and disorientation, drooling, sweats, numbness in the lips and extremities, nausea, muscle twitches, sleep, and a vague, often retrospective sense of liminal consciousness and waking dreams. At lower doses, none of these may manifest; at higher doses they may lead to coma and, on rare occasions, death.

Unlike the liberty cap, the fly agaric is hard to ignore or misidentify, and its toxicity has been well established for centuries (its name derives from its ability to kill flies). One could argue then that this aura of livid beauty and danger would alone be enough to explain its association with the otherworldly realm of fairies. Yet at the same time its mind-altering effects were becoming more widely known, not from any rustic tradition in Britain but from the discovery that it was used as an intoxicant among the remote peoples of Siberia. Sporadically through the eighteenth century, Swedish and Russian explorers had returned from Siberia with travellers’ tales of shamans, spirit possession, and self-poisoning with brightly-coloured toadstools; but it was a Polish traveller named Joseph Kopék who was the first to write an account of his own first-hand experience with the fly agaric, which appeared in an 1837 publication of his travel diary.

In around 1797, after he had been living in Kamchatka for two years, Kopék was taken ill with a fever and was told by a local of a “miraculous” mushroom that would cure him. He ate half a fly agaric and fell into a vivid fever dream. “As though magnetised”, he was drawn through “the most attractive gardens where only pleasure and beauty seemed to rule”; beautiful women dressed in white fed him with fruits, berries, and flowers. He woke after a long and healing sleep and took a second, stronger dose, which precipitated him back into slumber and the sense of an epic voyage into another world. He relived swathes of his childhood, re-encountered friends from throughout his life, and even predicted the future at length with such confidence that a priest was summoned to witness. He concluded with a challenge to science: “If someone can prove that both the effect and the influence of the mushroom are non-existent, then I shall stop being defender of the miraculous mushroom of Kamchatka”.5

Kopék’s toadstool epiphany was one of several descriptions of fly agaric use by Siberian peoples that were widely reported in various learned journals and popular works throughout Europe in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.6 Such accounts began a fashion for re-examining elements of European folklore and culture and interpolating fly agaric intoxication into odd corners of myth and tradition. This is the source of the notion that the Berserkers, the Viking shock troops of the eighth to tenth centuries, drank a fly agaric potion before going into battle and fighting like men possessed, regularly asserted not only among mushroom and Viking aficionados but also in text-books and encyclopaedias. There is, however, no reference to fly agaric, or indeed to any exotic plant stimulants, in the sagas or Eddas: the theory of mushroom-intoxicated Berserker warriors was first suggested by the Swedish professor Samuel Ödman in his Attempt to Explain the Berserk-Raging of Ancient Nordic Warriors through Natural History (1784), a speculation based on the eighteenth-century reports from Siberia.

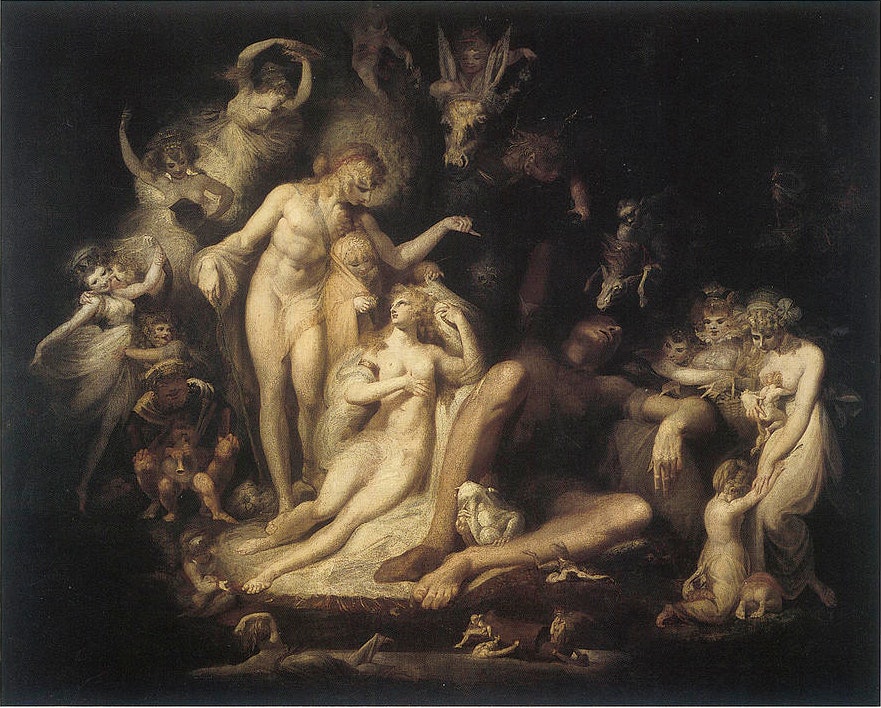

By the mid-nineteenth century, then, the fly agaric had become synonymous with fairyland. The mushroom had also, in the guise of the Siberian sources, been claimed as a portal to the land of dreams and written into European folklore. Exactly to what extent and in what manner these two cultural journeys of the fly agaric are intertwined is hard to pin down. Long before the Siberian accounts, in both art and literature, mushrooms of all sorts are depicted as part of fairyland. In Margaret Cavendish’s mid-seventeenth-century poem “The Pastime of the Queen of Fairies”, a mushroom acts as Queen Mab’s dining table, and in late eighteenth-century paintings by Henry Fuseli and Joshua Reynolds, the mushroom acts as a surface upon which fairies, sprites, and similar assemble. Such a presence of mushrooms in supernatural worlds might suggest a concealed or half-forgotten knowledge of hallucinogenic mushrooms in British culture. However, these fungi do not resemble fly agaric (or any other hallucinogenic mushroom) and, of course, for small woodland creatures the large splay of a mushroom would seem like natural furniture. It is only in the Victorian era, post-Siberian tales, that an hallucinogenic mushroom establishes itself so firmly in Britain as the stock mushroom of fairyland.

Let us turn now to the most famous and frequently-debated conjunction of fungi, psychedelia, and fairy-lore: the array of mushrooms and hallucinatory potions, mind-bending and shapeshifting motifs in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). Do Alice’s adventures represent first-hand knowledge of hallucinogenic mushrooms?

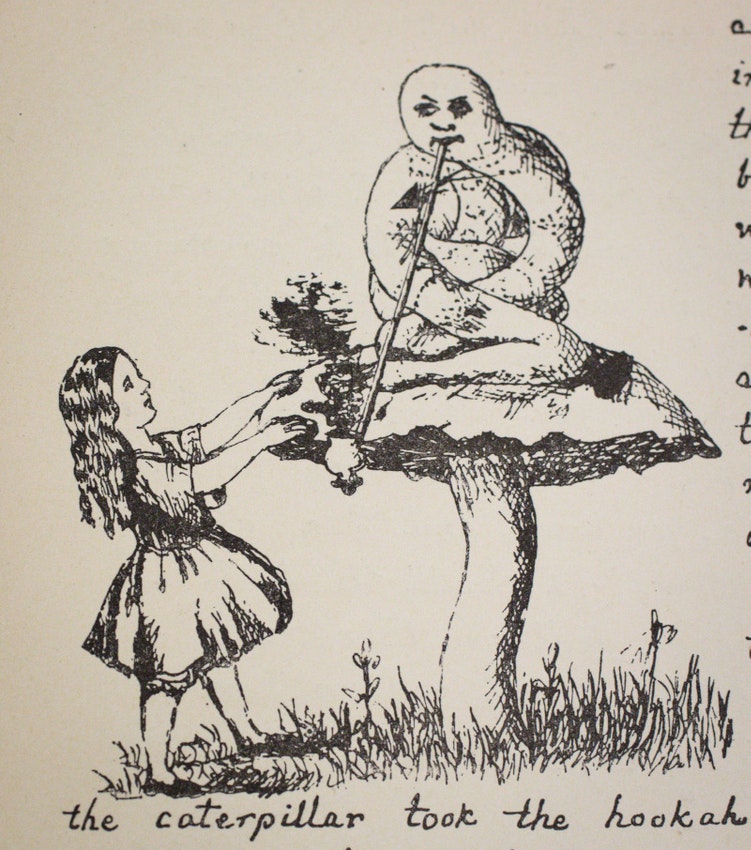

The scenes in question could hardly be better known. Alice, down the rabbit hole, meets a caterpillar sitting on a mushroom, who tells her in a “languid, sleepy voice” that the mushroom is the key to navigating through her strange journey: “one side will make you grow taller, the other side will make you grow shorter”. Alice takes a chunk from each side of the mushroom and begins a series of vertiginous transformations of size, shooting up into the clouds before learning to maintain her normal size by eating alternate bites. Throughout the rest of the book she continues to take the mushroom: entering the house of the Duchess, approaching the domain of the March Hare, and, climactically, before entering the hidden garden with the golden key.

Since the 1960s this has often been read as an initiatic work of drug literature, an esoteric guide to the other worlds opened up by psychedelics — most memorably, perhaps, in Jefferson Airplane’s psychedelic anthem “White Rabbit” (1967), which conjures Alice’s journey as a path of self-discovery where the stale advice of parents is transcended by the guidance received from within by “feeding your head”. This reading is often dismissed by Lewis Carroll scholars,7 but medication and unusual states of consciousness certainly exercised a profound fascination for Carroll, and he read about them voraciously. His interest was spurred by his own delicate health — insomnia and frequent migraines — which he treated with homoeopathic remedies, including many derived from psychoactive plants such as aconite and belladonna. His library included books on homoeopathy as well as texts that discussed mind-altering drugs, including F. E. Anstie’s thorough compendium, Stimulants and Narcotics (1864). He was greatly intrigued by the epileptic seizure of an Oxford student at which he was present, and in 1857 visited St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London in order to witness chloroform anaesthesia, a novel procedure that had come to public attention four years previously when it was administered to Queen Victoria during childbirth.

Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that Alice’s mind-expanding journeys owed anything to the actual drug experiences of their author. Although Carroll — in daily life the Reverend Charles Dodgson — was a moderate drinker and, to judge by his library, opposed to alcohol prohibition, he had a strong dislike of tobacco smoking and wrote sceptically in his letters about the pervasive presence in syrups and soothing tonics of powerful narcotics like opium — the “medicine so dexterously, but ineffectually, concealed in the jam of our early childhood”.8 Yet Alice’s adventures may have their roots in a psychedelic mushroom experience. The scholar Michael Carmichael has demonstrated that, a few days before he began writing the story, Carroll made his only ever visit to Oxford’s Bodleian library, where a copy of Mordecai Cooke’s recently-published drug survey The Seven Sisters of Sleep (1860) had been deposited.9 The Bodleian copy of this book still has most of its pages uncut, with the exception of the contents page and the chapter on the fly agaric, entitled “The Exile of Siberia”. Carroll was particularly interested in Russia: it was the only country he ever visited outside Britain. And, as Carmichael puts it, Carroll “would have been immediately attracted to Cooke’s Seven Sisters of Sleep for two more obvious reasons: he had seven sisters and he was a lifelong insomniac”.

Cooke’s chapter on fly agaric is, like the rest of his book, a valuable source of the drug lore that was familiar to his generation of Victorians. It refers to Everard Brande’s account of the J. S. family and rounds up various Siberian descriptions of fly agaric experiences, including details that appear in Alice’s adventures. “Erroneous impressions of size and distance are common occurrences”, Cooke records of the fly agaric. “A straw lying in the road becomes a formidable object, to overcome which, a leap is taken sufficient to clear a barrel of ale, or the prostrate trunk of a British oak.”10

The hypothesis is suggestive, though at this distance of time, it’s impossible to know for certain whether or not Carroll read this Bodleian copy, or indeed any other copy of Cooke’s book. It may be that Carroll encountered the Siberian fly agaric reportage elsewhere — we know, for example, that he owned a copy of James F. Johnston’s The Chemistry of Common Life (1854) which includes mention of fly agaric and size delusions11 — or it may be that he simply drew on the fertile resources of his imagination. But some contact with the widely reported Siberian cases does seem much more likely than the idea that Carroll drew on any hidden British tradition of magic mushroom use, let alone the author’s own. If so, he was neither a secret drug initiate nor a Victorian gentleman entirely innocent of the arcane knowledge of drugs. In this sense, Alice’s otherworld experiences seem to hover, like much of Victorian fairy literature and fantasy, in a borderland between naïve innocence of such drugs and knowing references to them. We read them today from a very different vantage point, one in which magic mushrooms are consumed far more widely than in the Victorian or indeed any previous era. In our thriving psychedelic culture, fly agaric is only to be encountered at the distant margins; by contrast, psilocybin mushrooms are a global phenomenon, grown and consumed in virtually every country on earth and even making inroads into clinical psychotherapy. Today the liberty cap is an emblem of a new political struggle: the right to “cognitive liberty”, the free and legal alteration of one’s own consciousness.

Mike Jay has written extensively on scientific and medical history. His books on the history of drugs include High Society: Mind-Altering Drugs in History and Culture and his most recent Mescaline: a Global History of the First Psychedelic.

PUBLISHED

October 7, 2020